How Russian language textbooks spread propaganda

Russia is actively pursuing a policy of Russification in the temporarily occupied territories, and education plays a pivotal role in this process. Schools are adopting Russian standards, using Russian textbooks, and retaining only teachers loyal to the “new government.” They exclude Ukrainian history, language, and literature from the curriculum while introducing Russian ideology. This strategy aims to erode Ukrainian identity and present Russia as the children’s motherland.

Russification has historical precedence, seen during the Russian Empire and Soviet period. Initially, there was a phase of “Ukrainization,” followed by the ousting of the Ukrainian language from culture, education, academia, and everyday life.

When Ukraine gained independence, Ukrainian was established as the state language, with official institutions and documentation switching to Ukrainian. In the early 1990s, Ukrainian became the primary language of instruction in most schools, although Russian still dominated in some areas.

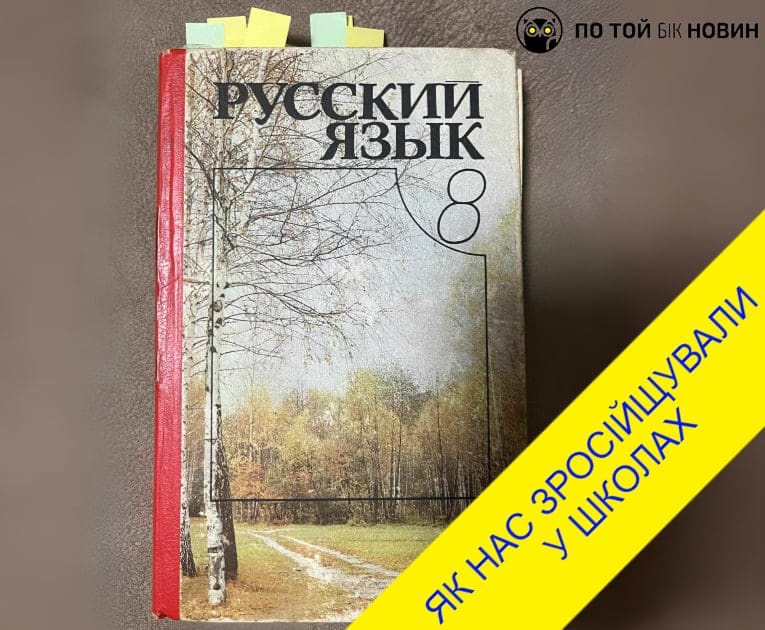

For instance, we came across an 8th-grade Russian language textbook used in Kremenchuk schools in the early years of independence. Before it ended up in the jungle of recycled waste paper, we decided to examine it.

Published in 1994 by Osvita Publishing House and approved by the Ministry of Education of Ukraine, the textbook was compiled by a team of four authors.

From the preamble, the authors steer students towards the “right” ideological direction, calling Russian the “native” language. They emphasize the necessity of knowing it not just for “writing and speaking” but for “influencing people with the power of words.”

In the introduction, the authors discuss the influence of the Ukrainian language on Russian and the differences between the two languages, but they present it dismissively. The authors highlight the Ukrainian influence in pronunciation, pointing to “the highest percentage of errors, such as the pronunciation of the ‘o’ sound and the fricative ‘h’.

In Yevheniya Kuznetsova’s book “Language as a blade. How the Soviet Empire spoke,” she explains, how the article “The Russian language in schools” advised teachers and textbook compilers to choose sentences that showcased “the power and greatness of our motherland.” Although this methodology was written before the Soviet Union’s collapse, the 1994 textbook follows the same principles.

The authors are persistent in their praise of the “motherland.” For example, on page 20, students are asked to read and analyze two texts to determine their themes. One text describes how “beautiful foreign landscapes” evoke images of the “motherland” that “make you feel all tingly inside so you can barely hold back tears.” The second text begins with, “one does not choose one’s motherland as a parent.” Given that these excerpts are from Russian Soviet writers, the reference to the “motherland” is clear, though it’s straightforward for us, adults.

Most of the authors whose works are used as examples in the textbook are Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Lermontov. Other authors included are lesser-known but ideologically “correct.”

1) Many people say, “We love the motherland.” These are important words, and one has the right to say them. But this right must be earned through work, study, struggle, and life.

2) It is impossible to think about Sevastopol without feeling a sense of courage and pride, your blood quickening in your veins.

3) Those who betray their motherland are despised by the people.

4) Whoever has never stood atop Ivan the Great, looked across our ancient capital from end to end, and admired its vast panorama has no idea what Moscow is truly like.

5) I want to live in such a way that I can give my motherland my last heartbeat, so that when I die, I can say I’m dying for my motherland.

6) The motherland – be prepared to stand up for it!

These excerpts demonstrate that students are taught not only syntax and grammar rules, but also the idea of the duty to sacrifice their lives for the “motherland” is implanted in their brains. The readiness to participate in wars on behalf of Russia against other states is embedded in Russian ideology and presented as patriotic education. A similar process is occurring in the education systems of the temporarily occupied territories.

The textbook encourages mastering coherent speech through descriptions of historical and cultural monuments. Every second description for consideration focuses on descriptions of either a Russian church or a “manor house” frequented by imperial writers.

“The Church of the Intercession of the Virgin was built on the Nerl River in 1165, one of the most beautiful architectural monuments,” and “Bartholomeo Rastrelli was an architect whose main works, palaces, and churches created in the mid-18th century, are distinguished by their extraordinary scale and splendor.”

“Pushkin loved the Russian countryside from childhood.”

“Rural landscape in Moscow Region. A clear winter scene,” etc.

Students are also tasked with describing architectural monuments in photos similarly. Interestingly, they are asked to describe the monuments in Kyiv, specifically St. Andrew’s Church and the Mariinsky Palace. Why? These were designed by Rastrelli, an Italian who lived and worked in the Russian Empire.

In another description, we found an intriguing note about the nature of the Chernihiv Region, containing the following sentence:

“…and it seems that somehow a Cossack strug appears behind the reddish promontory.”

The note clarifies that a strug is an “ancient Russian riverboat.” This explanation, suggesting that the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks sailed on “Russian” boats, reveals a propaganda narrative portraying Ukrainian history as intertwined with Russian heritage and emphasizing a shared historical and cultural legacy.

Essays and questions at the end of the school quarter are a distinct category. Children must demonstrate not only their grasp of grammatical rules but also their understanding of ideological principles. For example, students are asked to interpret statements such as:

“The smoke of the motherland is sweet and pleasant to us.”

“Be faithful to your motherland until your dying breath.”

“Do not be afraid of death – be afraid of defeat.”

Another task requires students to read a text and explain what the motherland is and how a moral person should treat the motherland, even if they see its shortcomings.

Additionally, students must answer questions like: Can a person who is indifferent to his or her country’s history and culture be called a patriot? In what life situations does patriotic feeling require a person to perform a special feat?

As illustrated, Russian textbooks play a crucial role in disseminating Russian propaganda. They are used to Russify and instill and strengthen Russian ideology in children. This approach was prevalent decades ago and continues today in the temporarily occupied territories ![]()

Prepared by Aliona Malichenko.