Russian propaganda at the Venice Film Festival

The 81st International Film Festival is currently underway in Venice, and the Ukrainian film community is using the platform to highlight the ongoing war in Ukraine. One example comes from the team behind the documentary “Songs of a Slowly Burning Land”, directed by Olha Zhurba, who organized an protest action to raise awareness about Ukrainian military and civilian prisoners held by russia.

The team appeared in embroidered clothing symbolizing the distance between Venice and eight locations where Ukrainians are detained in the so-called russia. Olha Zhurba explained that her goal was to unite two starkly different worlds: the world of art and life, and the world of torture and death.

However, like many high-profile events, the Venice Film Festival also features russian participation. While Ukrainians are using art to draw attention to the war, russian filmmakers have resorted to their usual form of communication - propaganda.

“Ordinary” killers

At the festival, russian filmmaker Anastasiya Trofimova presented a documentary titled “russians at War”, which portrays the everyday lives of russian soldiers on the frontlines in Ukraine. Trofimova spent seven months living with the russian military and now claims to be “telling their story.”

Trofimova says she aimed to show that these soldiers are ordinary people with families, a sense of humour, and their own perspectives on the war. The film offers brief glimpses of combat but largely omits the broader scale of destruction inflicted by the russian army on Ukraine. One soldier dismisses accusations of war crimes as “impossible,” and Trofimova herself asserts that she saw no evidence of such crimes during her time at the front.

The documentary has sparked outrage among Ukrainians, who see it as an attempt to portray russian soldiers in a sympathetic light. Despite this, international media and festival organizers have seemingly embraced the film as representing “different views on the same conflict.” Trofimova argues that “we should not incite hatred,” but instead seek mutual understanding between russia and the West.

In fact, this film, in its attempts to whitewash the so-called russia and show its military as “ordinary poor people,” is aimed at Western audiences. While the film is presented as an anti-war piece, it is part of a broader effort to spread russian propaganda. .

Why is this film considered russian propaganda?

If Trofimova’s previous work for russia Today isn’t enough to raise concerns, Ukrainian producer Dariya Bassel offers a more detailed explanation after reviewing the documentary.

For instance, Trofimova refers to the events of 2022 as the “invasion,” deliberately overlooking russia’s annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas in 2014. This framing suggests that the war only began in 2022, ignoring the fact that russia has been waging war against Ukraine for a decade.

Trofimova further claims that russia has not been involved in wars for a long time, conveniently “forgetting” russia’s numerous military interventions over the past 30 years, such as in Transnistria, Ichkeria (Chechnya), Georgia, and Sakartvelo. By portraying russia as a peace-loving nation, the film attempts to justify its current aggression.

The film opens with the story of a Ukrainian fighting for russia, creating the false impression that Ukraine is in the midst of a “civil war.” This narrative aligns with russian propaganda and distorts the true nature of the war, presenting russian aggression as an internal Ukrainian struggle.

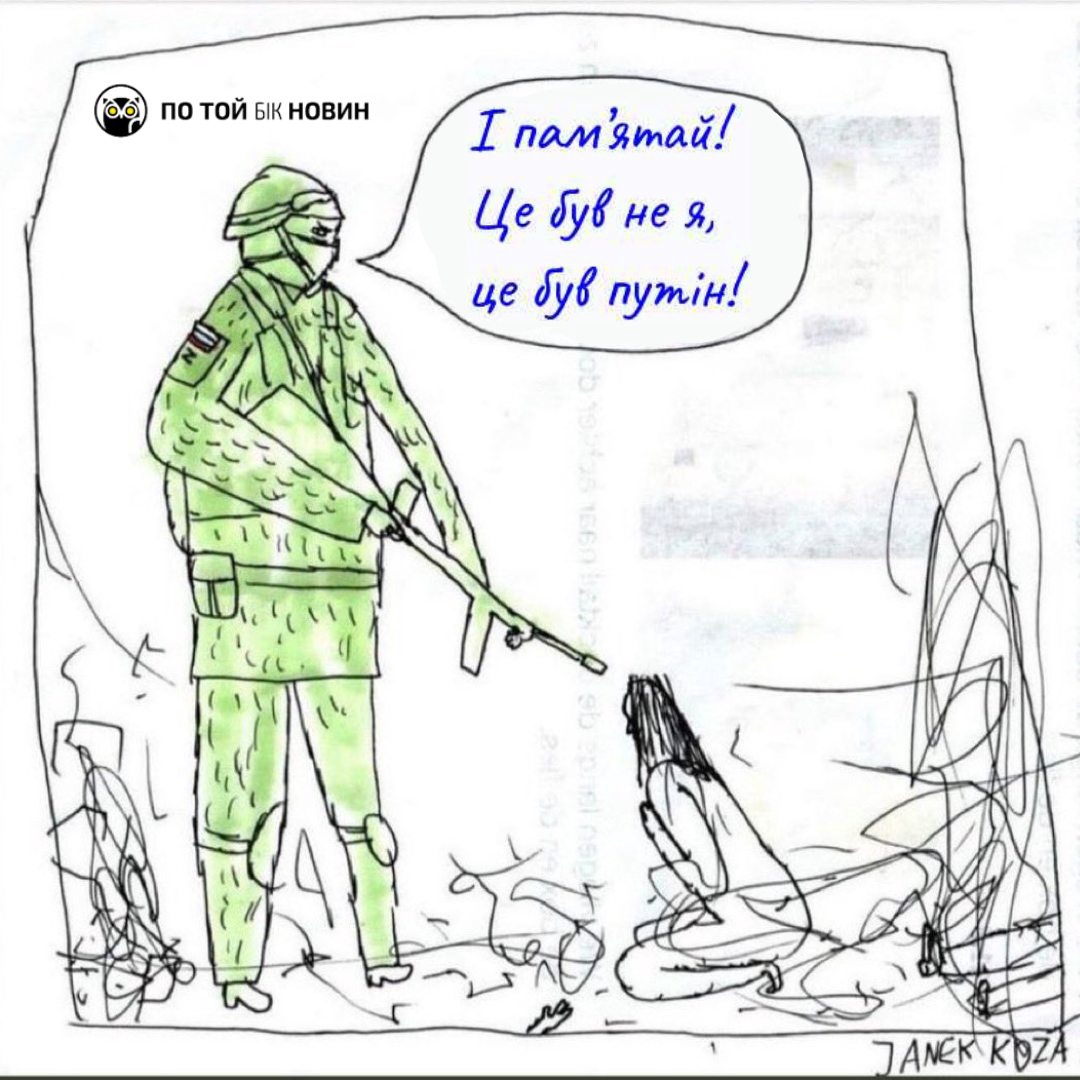

Throughout the documentary, the characters echo Kremlin propaganda, repeating claims that Ukrainians are bombing their own country or labeling them as “Nazis.” Meanwhile, the russian soldiers are portrayed as victims – in the film, they are ordinary people fighting not for an ideology but for money or because they’ve been manipulated. Their role in the aggression, as well as war crimes, is totally ignored, manipulating the audience to sympathize with the aggressors.

One of the film’s characters denies that the russian military commits war crimes, a stance Trofimova supports in her own comments. This stands in stark contrast to the documented evidence of russian atrocities, including the mass killings of peaceful civilians in Bucha, Mariupol, and Izium, as well as the forced deportation of Ukrainian children.

Selective focus

Trofimova also ignores the harsh realities faced by Ukrainians living under russian occupation in the regions she filmed. Interestingly, while she claims she did not receive permission from russia’s Ministry of Defense to remain there, she fails to mention that her actions violated Ukrainian law. After all, she was on Ukrainian territory, albeit under temporary occupation.

In fact, Trofimova’s film presents a skewed version of reality, overlooking the occupation and destruction caused by russia in Ukraine and portraying the soldiers of the country that started the full-scale war as innocent victims.

At a press conference in Venice, Trofimova was questioned about the ethical implications of humanizing russian soldiers, given the war crimes committed by the russian army. She responded by calling the question “a bit strange” and insisted that “everyone should be seen as human beings.” She described the war as “a huge tragedy for the region” and argued that viewing people through stereotypes only deepens hatred, adding that such views are the work of politicians, not ordinary people.

When asked if she had watched any Ukrainian films at the festival, Trofimova mentioned “Songs of a Slowly Burning Land” by Oksana Zhurba. She said she liked the beginning but took issue with the ending, particularly the contrast between Ukrainian and russian children. In the film, Ukrainian children speak of building a better Ukraine, while russian children “just marched and sang military songs.”

Trofimova lamented that this fed into the narrative that russians are inherently aggressive, saying, “I think it plays into the idea that russians are, by definition, aggressive and horrible people… that it’s in their blood to be like that.”

Canadian money

Interestingly, Trofimova’s “russians at War” was partially funded Canadian taxpayers. It should be noted that well-known Canadian producers Sally Blake, Philippe Levasseur, and Cornelia Principe, the latter of whom was nominated for an Oscar in 2024, took part in the production of the film.

Principe explained that the project initially aimed to explore russians’ attitudes toward the war. Originally, there were no plans to film at the front lines; the focus was meant to be on the internal situation in russia, especially amid its “growing information isolation.”

“I thought it was really important for someone from inside to tell what was happening to offer a perspective on this huge tragedy that basically started out of nowhere,” Principe said.

“russians at War” premiered at the Venice Film Festival as part of the non-competition program. After its debut, the film will head to another prestigious event, the Toronto Film Festival ![]()

Prepared by Aliona Malichenko.