The mechanics of russian cultural expansion

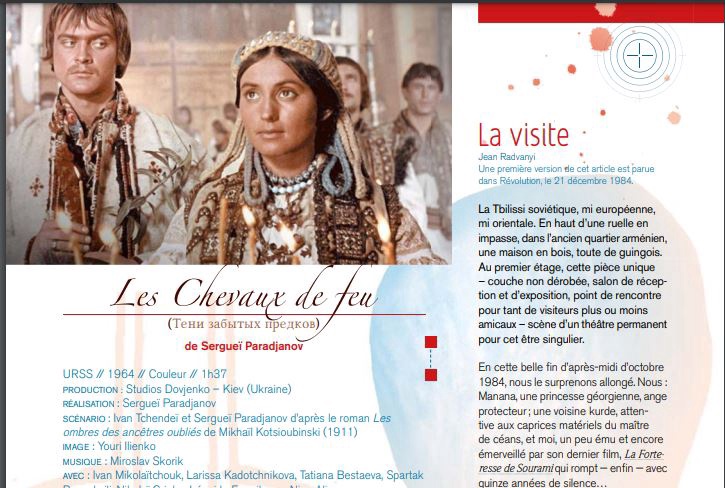

Among the films featured in the festival was Sergei Parajanov’s “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”. The inclusion of this Ukrainian film sparked a predictable response from the Ukrainian public, ranging from justified indignation to anger. Diplomats from the Ukrainian Embassy in France appealed to the French Ministry of Culture, objecting to the appropriation of Ukrainian cinematic heritage by the festival organizers.

The copyright for “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” is held by the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Film Studio in Kyiv. In a statement to UP.Kultura, the film studio confirmed that they had not received any invitations or communications from the festival organizers (no great surprise! russia steals, as usual).

The Ukrainian Institute in France also intervened, submitting an official appeal to the festival organizers. However, their request to remove “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” from the festival screenings was met with a refusal. The organizers justified their decision by claiming they were “staying away from the political struggle.”

Through this film festival, we aim to illustrate how russian culture serves as a potent weapon for russian imperialists, especially in countries like France. While we have not included links to the original articles and the festival program, they can be easily accessed if needed.

Cultural Offensive

Cinema, literature, ballet, and theatre are integral components of the “russian world,” employed as weapons to further russia’s imperial expansion globally. Following a well-established playbook, russians have invested heavily in establishing cultural institutions abroad, cultivating long-term relationships with foreign museums, foundations, scientific institutes, and local cultural figures.

These investments also facilitate the organization of exhibitions, festivals, and concerts that invite local audiences to appreciate the canvases of a “russian artist,” witness a “russian performance,” or view a “russian film.” This cultural expansion paves the way for shaping a benign image of the “other russia” - one that is cultural and innocuous. Such an image serves to not only justify russia’s aggressive actions but also to mitigate sanctions and evade accountability for russian crimes.

Moreover, 2022 demonstrated a substantial return on russian investments in cultural diplomacy. Many Western institutions now propagate the idea that artists should not be held responsible for their government’s actions, striving to foster reconciliation between russians and Ukrainians. Common statements like “Is Pushkin/Dostoyevsky/Tchaikovsky to blame for the war?” are frequently heard, and Ukrainians advocating for the assimilation of russian culture are often considered too radical.

Yet, russian cultural expansion is just as aggressive. It openly promotes russian “greatness” in comparison to other cultures. The director of the Hermitage Museum encapsulated this sentiment by describing russian culture as “a kind of special operation.” He argued that “cultural exports are more important than imports,” describing russian exhibitions abroad as a “powerful cultural offensive” aimed at dominating others.

In the same interview, the director of the Hermitage Museum openly acknowledged that the cultural offensive was timed to coincide with military actions. When the full-scale war erupted, exhibitions featuring collections from russian museums were showcased in France, Italy, the UK, and Spain.

However, it was the invasion that prompted the National Gallery in London and the Pushkin State Museum to terminate their collaborations. Since assuming her role in 2013, the russian museum’s director, Marina Loshak, has prioritized strengthening the museum’s connections with foreign institutions, a move described as “enhancing its international reputation.” This suggests that russia was laying the groundwork not just for the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine but also for broader international influence.

Additionally, the cultural landscape abroad was cultivated with the support of oligarchs and Putin’s associates. In early March 2022, the extent of this influence became apparent as to how far Moscow had spread its tentacles when several renowned museums and foundations worldwide severed ties with russians connected to the Kremlin.

The Guggenheim Museum and Foundation in New York parted ways with oligarch Potanin from its board of trustees. Oligarch Piotr Aven was removed from his trustee position at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and the museum returned a donation intended for a future exhibition. The Tate Foundation in London ended its support for Viktor Vekselberg, who had previously funded Carnegie Hall in New York before the US sanctions were imposed in 2018. In May 2022, the Pompidou Centre in Paris faced a scandal when it was revealed that the museum had received €1.3 million from Potanin’s foundation between 2016 and 2021. Following public outcry, as reported by Le Monde, the museum halted the third payment of approximately $619,000.

Another illustration of russian cultural expansion is the “russian Cinema” festival, initiated a decade ago (recall events in 2014).

The festival’s website identifies its founders as the “Other russia” organization. At first glance, the organizers may seem French, but a closer look at their backgrounds tells a different story. The honourary president is Macha Méril, referred to as a French actress and writer. However, she is the daughter of “Prince Gagarin,” a russian emigrant who fled the russian empire during the 1917 revolution.

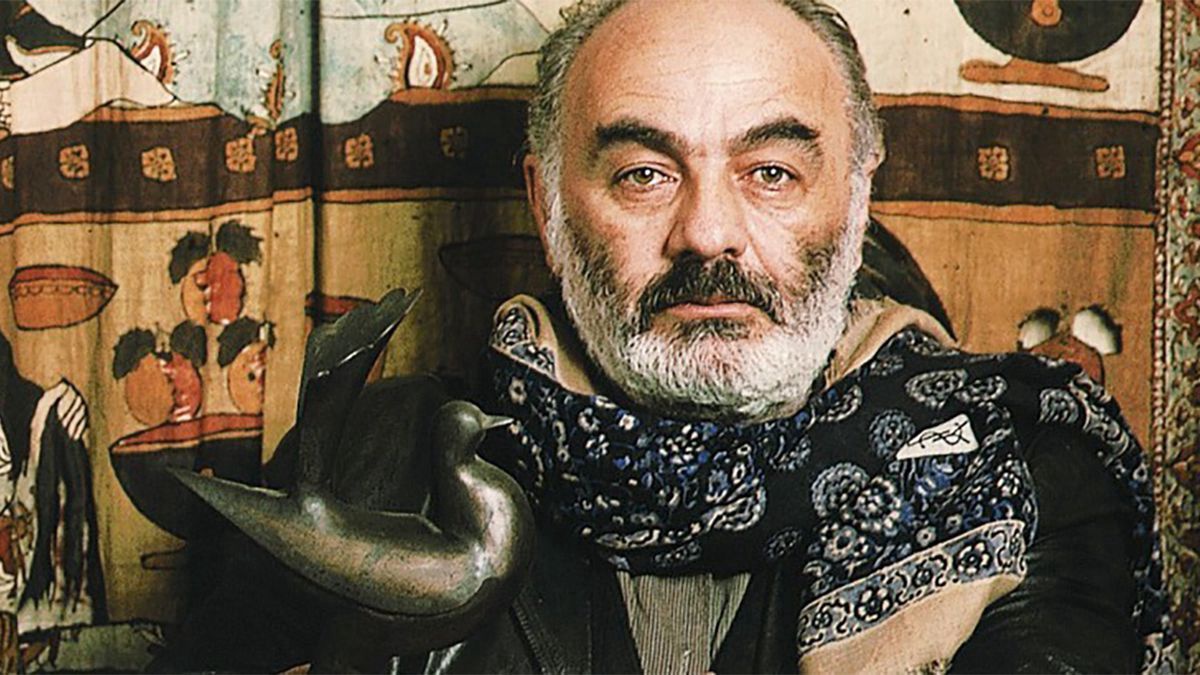

The organization’s president is Jean Radvanyi, a French geographer and geo-politician who initially focused on Soviet cinema in his career. However, his writings became increasingly specific over time, especially after his five-year stint leading the Franco-russian Research Centre in Moscow. Since 2013, he has authored books such as “Returning from Another russia: Immersion into Putin’s Country,” “Understanding russia: Challenges and Transformations,” “russia: The Dizziness of Power,” and “russia: Great Power, Weakened State.” The latter two were published in 2023. He has also participated in Valdai, a “discussion club” organized by russian authorities since 2004.

After a break “due to Covid and the war,” Jean Radvanyi traveled to russia via Georgia. Following this trip, he penned an article titled “Moscow, January 2024: A Peaceful Capital in a World at War?” In the article, he states that Moscow has improved during his absence, with little evidence of the ongoing war, restrained military propaganda, and a thriving military economy. He also expressed sympathy for his colleagues, film theorists isolated from the Western environment, while criticizing Putin’s policies.

Previously, another honourary president of the festival, alongside Macha Méril, was Jean-Pierre Chevènement, a French minister during the 1980s and 1990s. In 2017, he was awarded the Order of Friendship by Putin “for his services to strengthening friendship and cooperation between peoples, fruitful activities to bring together and mutually enrich the cultures of nations and peoples.” This accolade is a key detail to understanding this politician’s stance.

Until 2022, the festival of “russian Cinema” operated under a different name – “When russians...”. Each year, the program featured a new verb in the title, such as “When russians dream” or “When russians laugh,” etc. In March 2022, the festival “When russians travel” took place. For some reason or other, the organizers chose not to feature selections like “When russians kill” or “When russians rape.” Despite the full-scale invasion that year, the festival was held twice more (!), but under the name “russian Cinema”.

Following the festival’s name change, a new website also appeared. It seems that the founders aim to distance themselves from past support of the russian authorities. In 2024, the organizers expressed gratitude to their partners, the mayors of Paris and Taverny, and several patrons. However, the old website for the festival “When russians...” lists a much broader array of sponsors, including the russian embassy in France, Gazprom, Rosatom, and organizations like “Legends of the Kremlin” which were even featured on posters in 2016-2017.

Now, with such a background, the organizers are once again hosting a film festival. Their stated aim? To protect russian culture, particularly in cinema, “even in these turbulent times, despite the violence of the current government.” The festival program explicitly states that russian filmmakers “cannot be associated with the increasingly dictatorial government that governs their country.” In essence, the narrative that only Putin is to blame, while other russians are not, is being promoted once again.

Did the festival achieve its goal of distancing itself from russian aggression?

Regrettably, it did. The film screenings attracted an audience of 3,000 people. Moreover, the mayor of Taverny emphasized the festival’s significance against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine. However, there’s no reason to rejoice at her remarks. She asserted that it is the russians who currently need support: “The consequences of the war are significant in all areas, including culture. That’s why we believe it’s important and necessary to hear the free speech, past or present, of russian artists and intellectuals.”

Ukraine was mentioned only as a war-affected territory.

Appropriation of Cultural Heritage

Russian culture serves not only as a weapon to justify its aggression in the eyes of the Western world but also as a means to destroy and assimilate the cultures of other nations that russia considers “its own.” Kremlin propagandists employ culture to propagate narratives of a shared heritage with Ukraine while denying the existence of Ukrainian culture as such.

Culture shapes how the civilized world perceives countries and forms their image. Consequently, through these narratives, russia has effectively shaped an image of its “grand” historical past for decades, labeling Ukraine as an artificial state. Because without culture, there can be no national identity. Any breakthroughs by Ukrainian artists are either marginalized or appropriated.

Given this context, it is hardly surprising that the organizers of the “russian Cinema” festival included “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” in their screening program. Their choice seems to underscore the film’s significance to Ukrainian culture. Yet, according to Kremlin propagandists, Ukrainian culture is unable to stand alone and is portrayed as a mere extension of russian culture.

On September 4, 1965, during a screening of the film at Ukraina Cinema in Kyiv, a public protest erupted against a new wave of repression targeting intellectuals. The day prior, several Ukrainian artists, poets, and painters had been arrested. This event has achieved legendary status in Ukrainian history. In particular, the iconic phrase that launched the protest – “Who is for us, stand up in protest!” often attributed to Vasyl Stus. However, eyewitness accounts suggest that Viacheslav Chornovil was the one who actually shouted these words.

“Who is for us, stand up in protest!”

Sergei Parajanov himself was often a vocal critic of the Soviet government and its cultural policies. For his outspoken support of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, he was sentenced to five years in a strict regime camp on political grounds. It was only half a century later, in January 2024, that the distinguished director was posthumously rehabilitated in Ukraine.

Do the festival organizers in France acknowledge any of this history or even recognize the emergence of Ukrainian poetic cinema that began with “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”?

No, instead they describe Parajanov as an example of “the Soviet melting pot at its best” and as “an Armenian from Georgia, educated in Moscow to revive the vanished Ukrainian world.” As you can see, this portrayal starkly contrasts with Parajanov’s own well-known words identifying himself as “an Armenian born in Tbilisi who was imprisoned in a Soviet penal colony for Ukrainian nationalism.”

In general, the film’s description makes it challenging for the average European viewer to identify its ties to Ukraine. The film was produced in the Ukrainian SSR, yet Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi’s nationality is omitted; he is simply referred to as a writer. The characters Ivan and Marie (in the original), belong to two warring families. The story is set “in the past among the Hutsuls, the mountainous population of Bukovyna and Rus, in the Carpathians.” The only hint of Ukraine is the film’s place of production at the Dovzhenko Film Studio, but even this location is presented with the russian spelling “Kiev.”

The film owes much of its brilliance to the “nimble camera” of cinematographer Yuriy Illienko, with some suggesting that this work inspired him to become a director. However, Illienko, a classic master of Ukrainian cinema, is merely described as “a student of the genius Sergey Urusevsky.” One has to wonder how many people could readily answer, without resorting to Google, the question “Who is Sergey Urusevsky and what makes this russian cinematographer such a genius?”

The festival’s screening program also features a retrospective of three films by Larysa Shepitko. Born in Bakhmut and educated in Lviv, Shepitko studied at the Moscow All-russian State University of Cinematography (VGIK) - in Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s studio until his death in 1956. She made four films in russian. These two facts suffice for the organizers to label her as a russian director.

Not only did the festival steal our Ukrainian heritage, it also included two films by Otar Ioseliani. A Georgian director, Ioseliani lived and worked in France from 1982 onwards, having emigrated due to issues with Soviet censorship. What qualifies his cinema as “russian”? Once again, it is his studies at VGIK and the presence of russian dialogue in one of the films screened at the festival (the other being entirely in Georgian).

Both language and studies at a “prestigious capital” university serve as key indicators of the “russian world.” Regarding language, this aligns with a well-known russian policy: its influence ends where the russian language ends. As for VGIK, during the Soviet era (and even far into the 2000s in independent Ukraine), the prevailing sentiment was that the best opportunities lay exclusively in the “centre”, meaning Moscow. This notion imposed the belief that creative success could only be achieved by leaving the “provinces” in order to study in the russian capital. It was also easier to achieve recognition in one’s profession if one worked in Moscow and produced films (or wrote books, songs, etc.) in russian. These approaches enabled russia to russify representatives of other cultures and enrich its own “culture” with diverse talents.

Lastly, it is worth noting that our objections to the screening of “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” went unnoticed in France itself. We monitored local news media during the festival, but found no coverage of the Ukrainian protest rally. The only expression of our concern came from the institutions we initially mentioned (for which we are grateful). We found no statements or actions from the Ukrainian State Film Agency or the Ministry of Culture in response to this appropriation of our cultural heritage. It appears that the state institutions responsible for safeguarding Ukrainian cinema lack a strategy to counter russian cultural propaganda, while the russians continue to shape Western perceptions with their narratives ![]()