How to avoid manipulation of scientific research in journalism

This is a long and somewhat complicated but important text. Try to read it to the end. Your shares will help us get this information to as many people as possible.

“The study proves...”, “According to a study published in...”, “Scientists report...”, “The results of the study were shared...” These and similar phrases often appear in science-related articles.

Journalists, in pursuit of sensationalism and views, strive to present their readers with the most relevant and up-to-date information from the world of academia. Some media outlets even manage to publish materials about five to ten scientific “discoveries” every day.

All of this, of course, is accompanied by references to real research studies. It is considered bad form not to mention authoritative journals like “Nature” and “Science” in an article. After all, everyone has long since learned that each statement must be supported by a link to the original source.

A dispute in the comments about the benefits or harms of cannabis? Everyone has several links ready to prove their case.

But the devil is in the details, and today we will discuss these specifics.

We hope this material will be useful not only for journalists but also for anyone who wants to better understand the quality of research cited in journalistic articles.

Today, in PubMed (the bibliographic databases of the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the U.S. National Institutes of Health), you can find scientific papers to support almost any point of view.

PubMed, as noted in the parentheses, is not a journal, and scientists do NOT publish their research papers there. It is merely a specialized search engine - roughly speaking, akin to Google in the scientific world.

Currently, PubMed contains about 38 million scientific materials, and its database is growing every day. With this volume, it is possible to find support for almost any statement, even mutually exclusive ones, and then claim that they are based on scientific research.

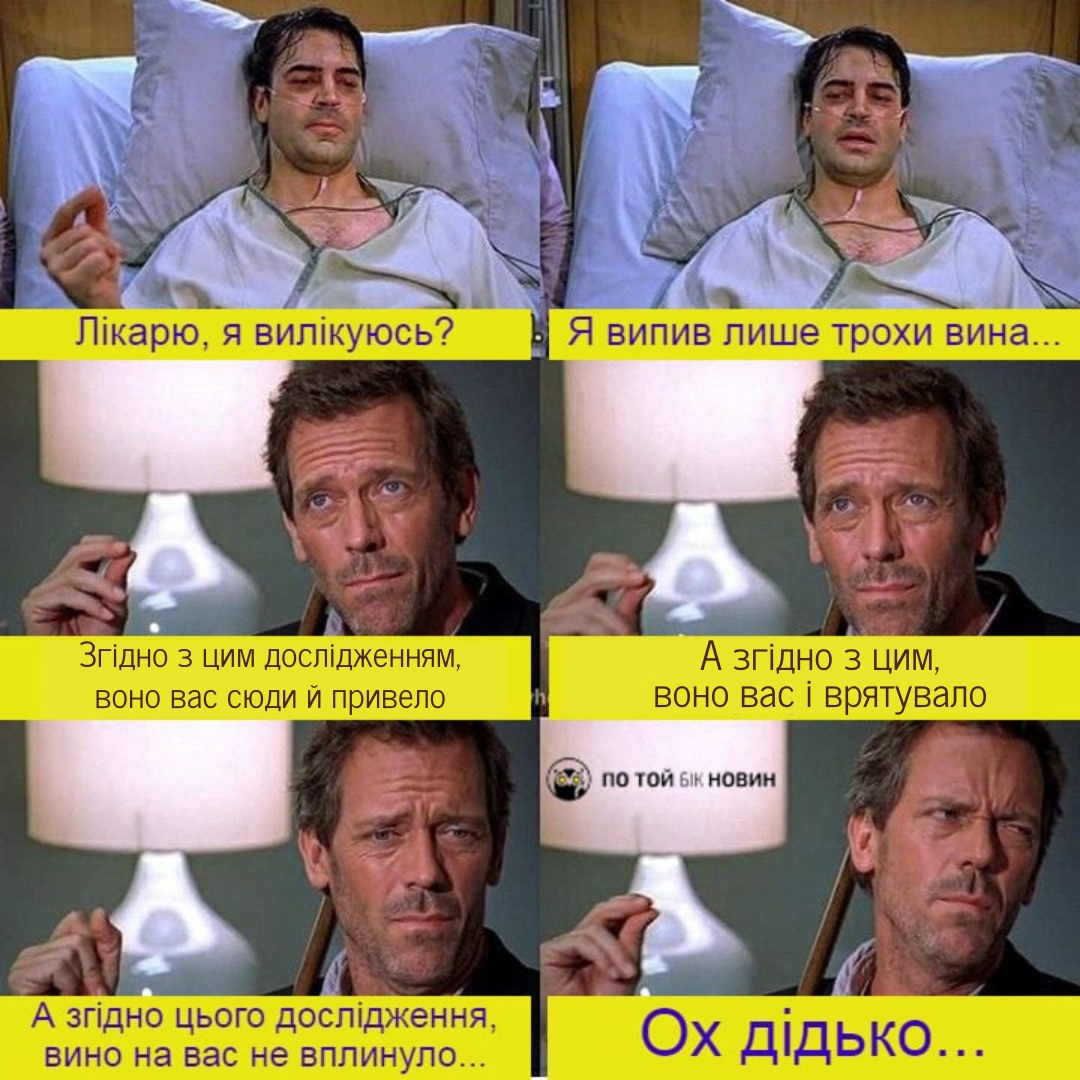

Let’s take alcohol, for example.

One study indicates that alcohol consumption increases cancer mortality [1].

Another study claims that there is no negative impact of alcohol on cancer risk [2]. Yet another study suggests that drinking alcohol is associated with a reduced risk of developing cancer [3].

Or consider tea:

One study says that drinking milk tea can lead to addiction, associated with depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts [4].

Another paper claims that tea can prevent the worsening of depressive symptoms [5].

Meanwhile, another study asserts that bubble tea (a type of milk tea) does not lead to addiction [6].

With such conflicting information, who should you believe? As always, the details are crucial.

Let us explain:

When you scroll through the PubMed database, you often see only an abstract - a summary of a scientific paper. Just a few sentences about the design, participants, conclusion, etc. But scientific research is a damn complicated matter with graphs, tables, and calculations, and the full text can span dozens of pages.

Typically, important nuances, limitations, and advantages of a research study are not always mentioned in an abstract. For example, the study might NOT be “blind” (participants might guess they are not taking the real medicine), or there might be a conflict of interest (the researcher receives funding from the manufacturer). Or it could just be a doctor’s notes on a single patient’s case.

Therefore, a journalist who reads only a short summary misses these crucial caveats, which can significantly affect the accuracy of the statement made in the headline.

A few words about the media, which publish daily reviews of dozens of articles.

Firstly, this format of presenting a large number of fresh scientific news poses challenges for authors as processing dozens of pages of complex research text is unlikely to be feasible.

Secondly, access to full texts is sometimes restricted, especially for the most recent research. It is doubtful that journalists invest funds in obtaining these materials. While it’s possible to bypass subscription fees in some cases, this would constitute piracy, and not everyone possesses the knowledge to do so.

Thirdly, reviewers of scientific discoveries sometimes engage in “the broken telephone” - that is, paraphrasing or translating reviews from foreign popular science media, such as New Scientist or Science Alert, into Ukrainian. Whether this practice is positive or negative is debatable, but foreign media outlets can also make mistakes and employ sensational, clickbait headlines. Everyone requires coverage.

The problem of press releases

Another issue in covering scientific news arises from press releases. Some journalists fail to verify whether a scientific paper has been published, relying instead on a few sentences from a conference presentation to report on another “sensational discovery.” Approximately 40% of press releases contain unsubstantiated advice, and some neglect to mention that the study was conducted on fish or rabbits rather than human beings.

Here’s a recent example.

In March 2024, several Ukrainian media outlets reported that the risk of dying from heart disease is 90% higher among those who practice intermittent fasting.

“During 2003-2018, researchers interviewed about 20,000 adult volunteers annually about their eating habits. The participants were monitored for eight years, including recording deaths among them and their causes. Thus, the scientists discovered that the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease increases significantly when intermittent fasting is observed, compared to more usual meals during the day,” stated the popular science publication nauka.ua. [7].

It sounds a bit too much, don’t you agree? And 90% is not such a small figure.

However, these high-profile data were derived from … a poster presentation at the American Heart Association Conference. The study was never published, and the claims made in it could not withstand criticism.

In truth, during 2003-2018, researchers interviewed participants about their eating habits only twice. Not twenty times during the year or even every year - only twice in 15 years! With reports from a two-day food survey, the researchers assumed that this eating pattern had been unchanged for all those years.

The researchers also did not know what the participants ate and whether they had ever heard of such a diet as “intermittent fasting”. Sleep patterns and shift work, which are associated with irregular eating, were also not taken into account.

After leading media outlets like the BBC, Washington Post, and NBC told the world that the risk of dying of heart disease was 90 percent higher with intermittent fasting, 34 scientific experts criticized the whole story and said that such thoughtless dissemination of information can only harm people’s health and undermine confidence in science [8].

Needless to say, the journalists who wrote those sensational headlines neglected to mention the subsequent refutation.

If you were to access the website of a scientific journal through PubMed or other means and even read the full research study, here are some tips on what to look for when reviewing it:

1. Type of Research

If the study is observational (describing specific events), it is usually impossible to establish a reliable cause-and-effect relationship.

Does drinking 2-3 cups of coffee positively correlate with IQ levels? We cannot conclude that coffee increases IQ or vice versa. It is likely that there is a third, unaccounted-for factor contributing to both higher IQ and the consumption of several cups of coffee per day.

Or perhaps it is merely a coincidence? The results of observational studies should be interpreted with extreme caution, and headlines such as “A glass of wine prolongs life” or “Emulsifiers cause cardiovascular disease” should be viewed with skepticism.

A misunderstanding of such studies contributes to statements like “studies confirm that the abuse of aspartame sodas increases the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer” [9].

2. Truthfulness

Ask yourself what the world would look like if the facts stated in the article were true. Do aspartame or milk truly cause a long list of diseases? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) would be addressing that issue loudly.

We would have seen warnings and a grim picture in numerous studies over the years. Incidentally, we wrote about the effects of aspartame on the body six months ago [10].

3. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Today, RCTs are one of the best tools for studying the cause-and-effect relationship between an intervention (medical treatment, diet, training, etc.) and the outcome.

Among the advantages:

randomization (random assignment of participants to one of the groups),

control group (helps to see what would have happened otherwise, e.g., without a certain medical intervention),

double-blinding (neither the researchers nor the participants know which group they are assigned to and who is taking the potential medication),

placebo (a tool that helps to simulate “noise” (spontaneous remission, improved mood from communicating with a doctor, the Hawthorne effect - the participant’s behavior changes when they know they are participating in the experiment).

All of this minimizes the influences that can distort the study’s results. While sometimes called the “gold standard” of clinical trials, RCTs also have limitations. For example, the results may not always be representative of the population. If only healthcare professionals or athletes were among the participants, then the data should be extrapolated carefully, as their lifestyle habits (nutrition, attention to health, rest, sleep) may differ from those of average people.

4. Interspecies transition

Don’t take to heart the results of research studies conducted on mice or drosophila. Did the study utilize cellular structures or computer modeling? Don’t extend the findings to human beings, especially not in such cases.

For example, the vast majority of results obtained in mice - about 90% - ultimately cannot be applied to humans. Unfortunately, reviews and abstracts do not always mention that the study was conducted on animal models.

5. Sample size

The smaller the number of participants in a study, the less reliable are its results. If, for instance, 15 athletes participated in a study and five of them were later eliminated, the study is of low quality due to the small sample size. Additionally, it is not always clear whether those five were eliminated due to non-compliance with the protocol, refusal to participate in the experiment, or whether they reported an effect that the researchers did not want to announce. All these details are important.

6. Funding

Pay attention to who funded the study. Cosmetic and food companies often conduct research for an already created product - they need at least some basis for marketing claims like “Scientifically proven!”.

Of course, ties with food companies do not always indicate dependence and dishonesty. However, even a hint of funding or a connection between a scientist and the industry raises doubts about their work. Is a yogurt manufacturer funding the research (let’s imagine that we are lucky and the scientists have honestly admitted this)? If so, we can expect a positive result and headlines about the benefits of the product for the heart or performance in sports.

7. Reporting

If scientists collected objective data (blood tests, body temperature), the results would be more reliable and objective than the results of studies where participants filled out questionnaires about their feelings, condition, or habits. Participants can lie, be biased, and their memory can fail them.

Imagine if you had to fill out a questionnaire about your eating habits over the past month. You probably wouldn’t remember what foods you ate, in what quantity, and when, and it wouldn’t be a deliberate lie. Inaccuracies in the questionnaire may even give the impression that you are on a diet or prefer a certain ingredient.

8. Replication

Find a replication of the study (reproduction of the results by an independent group of scientists) and compare its results with the findings of other studies. Seek the opinions of scientists who were not involved in the work. Usually, scientists react to the appearance of a high-profile and flawed study, but this reaction does not always appear in the first days of publication. Sometimes, you have to wait weeks or months. Such a long wait prevents journalists from writing scientific news with critical comments from scientists, as readers are eager for “hot” and fresh stories.

9. Scientific Journal

Pay attention to the journal where the study is published. There are so-called “predatory” media outlets that publish any nonsense and hoaxes for money. The Ukrainian media usually do not report on “discoveries” from these trash sources, but references to them can be found in articles about nutrition or bio-hacking. It should be remembered that authors can seek out any research study to support their opinions, and if journalists read only the abstract, they may not pay attention to the journal itself.

10. Pre-registration

Pre-registration shows the initial plans of the researchers. Review it to determine whether the researchers manipulated the data to obtain positive results and if they followed the rules of scientific experimentation.

If you discover that the study was sponsored by a food company, take the time to find the pre-registration of this work. Good scientists understand that pre-registration makes their work transparent.

Conclusions

All of the above-mentioned tips are not a panacea for problems in the research world, but they are better than nothing. Moreover, there are many loopholes through which some scientists try to publish low-quality work and trumpet it to the whole world. Yes, it’s not just journalists who want to publish a scoop; it’s also important for scientists to advance their careers and attract the attention of sponsors. It is quite difficult to detect these loopholes.

As soon as you come across the phrase “The study proves...” or “According to a study published in...,” immediately ask yourself: “When, where, how, and who proved it?” Don’t blindly believe in the results; these are not sacred texts.

If you found this post useful, we would be grateful for your likes, comments and reposts ![]()

Prepared by Dmytro Filipchuk.

Links:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21403041/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19932648/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19957334/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37625703/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33575719/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36569608/

- https://nauka.ua/.../rizik-pomerti-vid-sercevoyi-nedugi...

- https://drive.google.com/.../1sMUMe.../view

- https://life.liga.net/.../marketynh-chy-pravda-diietolohy...

- https://www.facebook.com/behindtheukrainenews/posts/pfbid0P2LmS9kbcEGKsNobSzvUCadZsn3NAwvNJPwqAu4SCxDbh3zMotMAXwYeipujytbhl

- https://uk.wikipedia.org/.../%D0%93%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE%D1...